Note: I wrote this paper for my first Biology lab course at CU Denver. I got a 200/200 score on the paper, as well as an email from the TA telling me I ought to reach out to someone called professor Hartley for more opportunities to research squirrels (and other animals). I'm still struggling to process/accept such glowing feedback, but I guess I'm gonna have to take the damn compliment eventually.

Below is the paper I wrote for my Squirrel research project (AKA SquirrelNet). The formatting's a bit screwed up here, but it is what it is:

Introduction:

Denver, Colorado is a large, dense city located along the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, where the air is dry and the weather is unpredictable (The climate, 2025). Denver is a highly urbanized environment, meaning that most of Denver is comprised of clusters of huge, multi-story buildings surrounded by concrete, asphalt, and non-native foliage (Mccleery et al. 2010). On top of that, roughly 716,577+ people live in the city of Denver, Colorado as of 2023 (Quick facts, 2023).

Unfortunately, many of Colorado’s wild animals have struggled to adapt to Denver’s ever-growing population and expansion. As more and more natural land gets swallowed up by Denver and urbanized, many wildlife move out of the way and fail to adapt. However, a few species have managed to adapt to the city life in Denver, such as squirrels and geese. For this project, we specifically studied Fox Squirrels (Sciurus niger), which can be found all throughout the United States, including in downtown Denver (Mccleery et al. 2010).

To study Fox Squirrels, we used the Optimal Foraging Theory, which states that all animals try to gather as much resources as possible, while expending the least amount of energy as possible (Tyson et al. 2016). Many animals, such as Fox Squirrels, are known as central-place foragers, meaning they try to forage for food as close to a safe place as possible as quickly as possible (Tyson et al. 2016). In other words, Fox Squirrels like to forage close to trees and buildings, because they can get away from predators more easily if they’re close to something they can climb.

The presence of huge, mature trees and large buildings make Denver’s Auraria campus a perfect environment for Fox Squirrels to survive. Plus, Fox Squirrels can find plenty of food on campus, especially during the fall and spring semesters when students are living (and eating) on campus. Therefore, the Auraria campus has more than enough squirrels for students like myself to observe, making them an excellent target species for this study.

Like all scientists, we were tasked with formulating a research question and a hypothesis. We came up with several research questions, including, “How do squirrels behave on campus?”. Soon enough, we came up with the hypothesis, “If there are fewer people around, Fox Squirrels will exhibit more foraging behaviors vs when there are more people around.

Methods:

Studying the behavior of Fox Squirrels is important because so many people coexist with Fox Squirrels in Denver. Some people like having Fox Squirrels running around, while other people do not, and Fox Squirrels have surprisingly not been studied very much in urban environments (Mccleery et al. 2007). Plus, Fox Squirrels have adapted remarkably to the city life, which means that studying them will help us learn what it is that makes Fox Squirrels so adaptable, and may even help us figure out how to make our cities friendlier to other, much less common wildlife (Mccleery et al. 2007).

To study Fox Squirrels on Denver’s Auraria campus, we printed out a Squirrel Behavior Observation Datasheet (SBOD) to take with us as we looked for a squirrel to observe on campus. Once we found a squirrel, we waited five minutes before conducting any other observations to allow the squirrel to get used to us being there. During this time, we filled out the first three sections of the SBOD, in order to document exactly where and when we were observing our squirrel, as well as information pertaining to the weather.

Once the five minutes passed and the squirrel was acclimated to our presence, one person played the role of observer, while the other kept track of time and documented the squirrel’s behavior. Part four of the SBOD includes a chart that has six categories of squirrel behavior: Vigilance, Foraging, Alert Feeding, Social, Other, and Not Available. Vigilant squirrels tend to stand still and look around for predators. Squirrels who are foraging are focused on finding food by digging or chewing on twigs and nothing else. Alert foraging squirrels sit/stand while chewing on something they found. Social behaviors describe squirrels who are interacting directly with other squirrels. Other behaviors are miscellaneous behaviors a squirrel might be exhibiting, such as running up a tree or grooming itself. And Not Available describes if/when the observer temporarily loses sight of the squirrel. Every twenty seconds during a five minute period, the observer would call out a category that accurately described the squirrel’s behavior, and the documenter would document it on the SBOD.

At 12:46 PM, I began to observe the squirrel while my partner, EV, watched the time and filled out part four of the SBOD. For five minutes, I observed the squirrel’s behavior, during which I called out what it was doing every twenty seconds. At 12:51 PM, I stopped observing the squirrel, and we headed back to the lab to record our results.

Upon returning to the lab, we were given access to a massive SquirrelNet database containing all published data from when SquirrelNet was first started, and asked to analyze said data based on our hypothesis. As mentioned previously, we hypothesized that squirrels forage for food more when there are less people nearby. Therefore, we only analyzed two bits of data: the number of people present, and the number of foraging behaviors exhibited by a target squirrel in a five-minute period. Every twenty seconds, we would write down exactly what the squirrel was doing at that moment, equating to sixteen total observation data points.

Results:

Because there was so much raw data in the SquirrelNet database, we had to organize our table (Table 1) by averaging out the number of humans present, compared to the total, unaveraged sum of squirrel foraging behaviors recorded during the five minute period. For instance, if the squirrels only exhibited two instances of foraging behaviors during the five-minute observation period, we’d average out all of the humans present each time squirrels only exhibiting two instances of foraging behaviors in a five-minute period. Neither Table 1 or Figure 1 include Alert Foraging behaviors in the data. We only included Foraging behaviors in the data. Below is the table we created:

Table 1. Average Number of Humans Present vs Average Number of Squirrel Foraging Behaviors. Here is a table displaying the total foraging behaviors of Fox Squirrels vs how many people were present, on average, during the five minute observation period. Due to the large amount of data points, we organized the data so that for each survey where Fox Squirrels exhibited a certain number of Foraging behaviors within a five-minute observation period, we averaged out the number of humans that were present.

|

Total foraging |

Average number of humans present |

|

0 |

6.220902613 |

|

1 |

7.126623377 |

|

2 |

5.248677249 |

|

3 |

5.201438849 |

|

4 |

5.052380952 |

|

5 |

5.035175879 |

|

6 |

4.210023866 |

|

7 |

5.293375394 |

|

8 |

4.372483221 |

|

9 |

4.692913386 |

|

10 |

4.75879397 |

|

11 |

3.746666667 |

|

12 |

3.696969697 |

|

13 |

4.188679245 |

|

14 |

3.082191781 |

|

15 |

6.1875 |

|

16 |

10 |

We also created a graph (Figure 1), that illustrates this data as a scatter plot with a trendline:

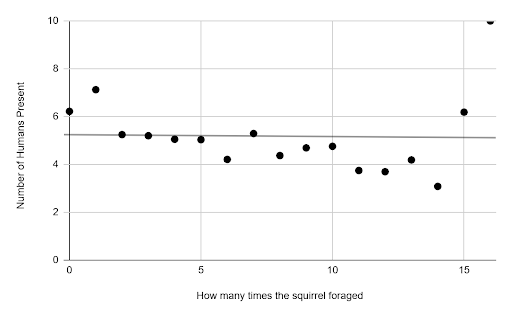

Figure 1. A Scatter Plot visualizing Fox Squirrel foraging behaviors in the presence of humans. The scatter plot above shows the average number of times a squirrel exhibited foraging behaviors within a five minute compared to the average number of humans present while that squirrel was exhibiting foraging behaviors. We included a trendline to help us visualize the slope of the data, which is nearly flat. A flat trendline indicates little to no correlation between the Number of humans present and how many times the squirrel foraged.

Discussion:

As mentioned before, the data recorded in Table 1 compares the average number of humans present compared to the number of times squirrels exhibited foraging behaviors during the five-minute observation period. As mentioned before, due to the vast amount of data that has been collected over the years, we organized Table 1 in such a way that shows the average number of humans present, compared to every instance where squirrels exhibited a specific number of Foraging behaviors within a five-minute period. Table 1 does not include Alert Foraging behaviors. It only includes Foraging behaviors, which means that the target squirrel was spending most or all of its energy searching for food, rather than watching out for predators or other squirrels.

We collected this data to determine whether or not squirrels will Forage for food in the presence of humans, as well as whether or not their foraging behaviors are impacted by the presence of humans. In other words, we hypothesized that squirrels would exhibit fewer instances of Foraging behaviors in the presence of humans, than they would if there were no humans present.

Based on Table 1, we concluded that we cannot determine whether or not the presence of humans impacts squirrel Foraging behaviors.

After all, many squirrels exhibited 0 Foraging behaviors within a five-minute period when there were, on average, roughly 6 people present (Table 1). However, according to the data, there were instances where squirrels Foraged for the entire five-minute observation period while there were an average of 10 people present (Table 1). Also, Table 1 consistently shows that squirrels exhibited Foraging behaviors when there were between 4-7 people present, on average, during the five-minute observation period (Table 1).

To represent Table 1’s data in a more visual form, we created a scatter-plot (Figure 1), to make it easier for us to discuss the results of our study. As we can see, there are points all over Figure 1, ranging from 3 instances of squirrel Foraging behaviors observed during a five-minute observation period, to 10 instance of squirrel Foraging behaviors observed during a five-minute observation period. Neither of those numbers seem to be impacted by the average number of humans present during those times Fox Squirrels were observed Foraging for food. In fact, the trend line is nearly flat, indicating little to no correlation between the number of times Fox Squirrels Foraged for food in five-minute period, and the average number of humans present while Fox Squirrels were Foraging for food (Figure 1).

When researching our hypothesis prior to analyzing this data, we discovered that there are almost no other studies that talk about how humans may or may not directly impact the Foraging behaviors of Fox Squirrels. The only study we found focused on the survival rates of Urban Fox Squirrels vs Rural Fox Squirrels, which showed that Urban Fox Squirrels survived more than Rural Fox Squirrels, despite- or maybe because of- the constant presence of people (Mcleery, et al. 2010).

However, there are many studies that have documented the impacts of urbanization on other kinds of wildlife. For instance, birds that live in heavily polluted environments experience greater stress and higher mortality rates than those who live in much cleaner environments (Santicchia, et al. 2024). Light pollution has also been found to significantly impact wildlife behavior in urban environments (Santicchia, et al. 2024). But, nobody has studied how air or light pollution impact Fox Squirrel’s health and/or behavior.

In other words, more studies should be conducted that focus specifically on studying Fox Squirrel Foraging behaviors in the presence of humans, to determine whether or not humans have a positive or negative impact on squirrel Foraging behavior. Especially since neither Table 1 nor Figure 1 could illustrate a clear correlation between the number of humans present, and the number of times Fox Squirrels Foraged for food.

- Prev

- Next >>