I’ll always remember that old cornfield, that’s right across the road from a rather new middle school. It’s where the hooves of many horses I’ve known have galloped. From an old red bay called Peter, to a spunky chestnut roan called Smudge, to a patchy red paint called Apache.

My grandpa once raced his brother in Peter's saddle in that corn field. His brother was on Apache. Apache was younger and theoretically faster, but in that old cornfield right across the road from a rather new middle school, that old spirited bay won the race by ten yards or so. My grandpa’s brother is more of a cowboy than my grandpa, but even he couldn’t get Apache to win the race against my grandpa Lyle in old Peter’s saddle.

Peter was my favorite. When I rode him, Peter was always careful, but he still went as fast as I wanted him. I never rode past a trot when I was younger, mostly because I couldn’t reach the stirrups. I used to race my older cousins who always rode Apache or some other horse they brought over. When I finally started to canter as I learned how to ride an english saddle, old Peter’s lungs got infected, and he was put down. I was very sad, but I decided that my riding days were far from over, and it was time for me to tame Apache.

Old Peter was still around the first time I rode Apache, but Apache was such a spookable horse back then, that when I tossed a coat to get it over my shoulders, I ended up landing in the dirt face-first after holding on for almost two bucks. I was fine, albeit it I had a mouthful of blood and mud, but I walked away that day, scared of riding Apache. My uncle Courtney gave me my first cowboy hat that night and told me to wear it with pride. Several years later, old Peter died, so I had to ride Apache, who had calmed down considerably by then.

I started by working Apache on the ground. My great uncle Courtney taught me how to command 1,000 pounds of galloping steed, with just the flick of the rope and a step of a boot. I’d stand in the middle of the round pen, spinning a rope in my hand. Apache ran around me as fast as I wanted him to, and when I wanted him to change direction, I’d take a risk by stepping out in front of him and flicking the rope lightly towards him. He'd skid as he turned around, and would almost always begin the next few laps bucking. There were a few times where I felt the wind of his rear hooves against my face, and Courtney would always react with a smile by saying something like, "Woah, you better give him some room next time!"

After a few laps in both directions, I’d step in Apache's way and walk towards him as he skidded to a stop. With a soft voice and gentle touch, I’d get him to stand so I could clip the reins on his bit and get in the saddle. By then, I could stand in the stirrups, and Courtney was always proud.

After a couple years, I started getting bored of Apache, because age was slowing him down. He was still a good horse, but he never rode past a slow trot, and his back was beginning to sway. Years of seasonal hunting trips takes a toll on a packhorse like Apache.

A new horse was introduced to the family. His name was Smudge. He was a wild and young chestnut roan who was even more spookable than Apache was. It took forever for me to gain the courage to ride him.

I ended up going to english riding lessons for a year. I enjoyed it for the most part, but it just wasn't my style. I didn't like the helmet, the feel of the saddle, or the way I was asked to hold those pretty pink reins. I got bored of that same old indoor arena I rode in every weekend. My horse was so predictable that by the 5th lesson we rode without too much thought. My teacher did her best to keep it interesting. I was a fast learner, so I was cantering, riding sideways and even backwards in the saddle, and doing small jumps in almost no time, but I missed the western style of riding. I got some useful experience out of that year, and I definitely gained some courage, though not enough to jump on a wild horse like Smudge.

I only gained the courage to ride Smudge after I went to North Dakota for the first time. There, a neighbor called Steve invited me and my grandpa Lyle to ride one morning. Steve is exactly who you see when you picture what a cowboy is. He breaks his own horses, and has stuck to the old timey ways of working cattle. He even has a clever cattle dog who follows him wherever he goes.

The morning we arrived, Steve already had three horses saddled, and was standing in the shadow of his antique white barn. He wore a feathered brown cattleman’s cowboy hat and dusty, horn scarred chaps. His pointy-eared companion sat panting next to him, ready and waiting to work. I looked around for a round pen, but didn’t find it anywhere on the property. I saw the stockyard, the pasture, the barn, the house, and the greenhouses, but there wasn’t a round pen in sight. Steve saw that I was looking around for a place to ride, and he came up to me with a pretty chestnut gelding, and told me to get on because we were gonna ride on the young croplands of the North Dakota hills. I noticed the chestnut didn’t appear to have a bit, only a rope bridle with some leather reins clipped to some rawhide loops. I stared at Steve for a moment while I processed what he said, but I didn’t question it. I knew those eyes under the brim of that worn leather hat were serious. Cowboys don’t have time for pranks or lies.

Once I was fitted into my saddle, Steve walked over to his identical buckskin mares and untied them both. He handed one to my grandpa, and got on the other. Those mares were wild! They hadn’t been ridden since the fall before, and it was nearing the Fourth of July that morning. My horse was apparently hungry, because the bitless bridle did nothing to stop him from wandering across the road and into the grassy ditch while I did everything I could think of to get his head up. Meanwhile, on the road, the boys struggled with the mares, and it was minutes before Steve had his under enough control to rescue me. He simply grabbed my horse’s bridle, dragged him out of the ditch, and showed me how to hold the reins right. I was so used to english riding, that I almost forgot how I started off. I was born to ride a western cowhorse, not some posh british show steed with pretty pink reins.

From the road, we trotted into a barren crop field, and up the crest of the hill. From there, we paused to scan the North Dakota countryside. To the northeast, we could see the Garrison dam, and not far from it, we could just barely see Riverdale. The farmland between us and the dam was dotted with green, yellow, and barren brown fields, along with tall blue silos, large white barns, and red tin granaries. Trees were scarce, the land was flat below us, and the skies were without clouds, so we could see a very long way, almost completely across lake Sakakawea in fact.

Eventually, Steve turned to the right, and grandpa, I, and Steve’s dog followed him. Steve trotted ahead of us, and even cantered a bit. This excited all of our horses and the dog, and I decided it was now or never. I either got left behind, or I stood in the stirrups and kicked that chestnut cowhorse into a canter. After crossing a small irrigation ditch, where I lost sight of the guys over the crest of another barren hill, I stood in the stirrups, leaned a bit forward, and held the reins just a bit forward. I didn’t even need to give my horse a kick to the sides, because he knew exactly what I wanted him to do.

I caught up to the two guys in no time, who were trotting their frisky mares stirrup-to-stirrup. Steve only glanced back a quick second to make sure those cantering hooves belonged to my chestnut gelding. I took my seat back in the saddle and relaxed a bit. My horse’s trotting gait was soft enough for me to comfortably relax, before my english riding training kicked in and I stood up and down with my horse’s trot.

We were in the saddle for another hour, crossing over irrigation ditches, some flooded, some dry, squeezing between barbed wire fences that were almost too narrow for us to ride by without getting our jeans and stirrups pricked, and ascending and descending hills on barren croplands. At times, a horse would dart off in a random direction, and everyone else would follow. At one point, I noticed Steve had a lariat around his saddle horn. He later said he was willing to use it if we played cowboys and indians a little too hard and one of us got bucked off, and we each came close at one point or another. My grandpa’s horse was especially wild. We eventually made our way back, all three of us stirrup-to-stirrup, where Steve’s wife stood on the front porch waiting for us with water.

We dismounted our horses by the old white barn, and took the saddles off their sweat-drenched backs. We brushed the sweat off their backs, picked the gravel out of their hooves, and Steve rubbed some anti-fly cream in the horses’ ears. After that, each of us took the lead of our horse, and led them to the main pasture where Steve kept two other horses. He had an old swayback chestnut mare who was the mother of my horse, and a young dark bay who wasn’t yet saddle broken. He gave each horse their own pile of oats, and we left the exhausted horses to rest in their pasture. The last thing Steve said to me before I got in the car was, “You better get yourself a cowboy hat and wear it with pride!”

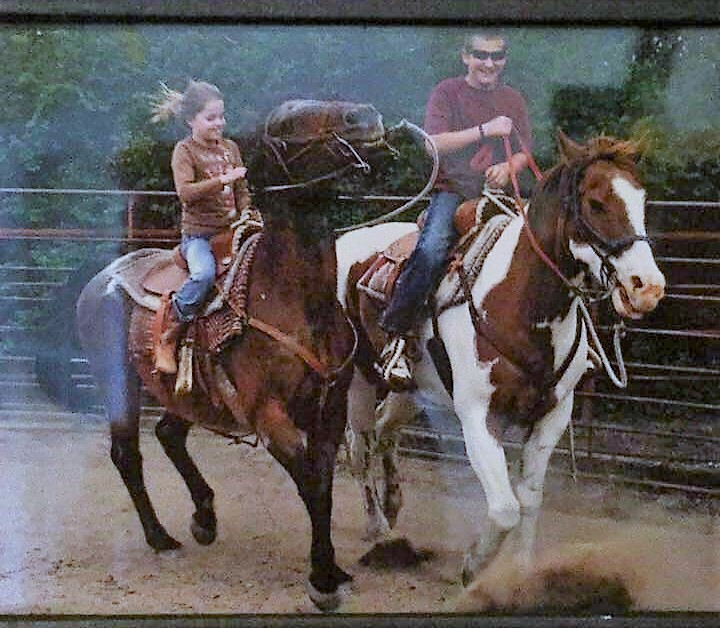

I returned to Colorado soon after, with a confidence I thought I could never have. I ended up back at Courtney’s, ready to ride the trails on Smudge that time, but I still somehow ended up in Apache’s saddle, and my grandpa in Smudge’s. Nevertheless, Courtney led us on the bridle path on foot, while we stood in the stirrups in our slow, squeaky leather saddles. The horses were spooked often by barking dogs and mares that came up to the fences with their ears pinned, but not so much that we couldn’t control them. I think Courtney’s lead helped a lot to keep the horses calm.

Eventually, we ended up at the old cornfield where every horse Courtney’s ever owned has been raced at least a few times in their lifetime. I knew who would win that race. Smudge was like old Peter; wild and spirited. Apache was slowing down, and would rather rest than run. I was still happy to be in the saddle, even though my grandpa was at the other end of the field before Apache and I were halfway. I met him there, and we trotted back, stirrup-to-stirrup, riding rather close to the parallel road, though the horses were never afraid of vehicles. Courtney led us back to his place, where we took off the saddles, brushed the sweat off our horse’s backs, and led them back to their pen for the day.

That winter, I ended up back at Courtney’s, and while I had a chance to ride Smudge, Smudge was acting very nervous. In fact he was so nervous, he almost kicked my ass to heaven when I was trying to work him out in the round pen on foot. After that close call, I just decided that it was a Divine sign I better get Apache and ride him instead. It was still a good ride even though it was 15 degrees outside with a windchill of -5, and Apache was almost as frozen as I was.

One month later, I went to the annual stock show with my grandpa and little brother. My little brother wasn’t nearly as entertained as I was. Unlike him, I love to check out the show livestock, especially since showing steers and prized hereford bulls at county and national fairs is in my blood. I found a cattleman’s cowboy hat that looked almost identical to Steve’s and payed for it. The only difference was mine was made out of white canvas while Steve's was made of brown leather. It didn’t come with a feather, but on the way back to the car on the first day of the stock show, I found a stray peacock feather tip on the ground that was surprisingly dry and clean, so I shoved it into my hatband.

I returned for the rodeo the next day, where my little brother complained a lot less. You can’t possibly be bored when you’re watching rodeo legends ride legendary bulls, and people performing crazy stunts on galloping horses with no saddles or bridles. There was one injury that day, and that was because a teenage girl’s barrel horse slipped and rolled over on top of her, but we later found out she was discharged from the hospital and expected to make a full recovery.

Summer rolled around again, and my mom and grandma wanted to treat me to a trip to Los Cabos, Mexico. I’ve never been to Mexico before then, though I’ve been to a couple other countries and traveled from coast-to-coast in my own. I was excited to rest on the resort beaches for a week. I was even more excited when I had the opportunity to ride horses on the beach. My mom and grandma were terrified, but they did it for me.

We took a tour bus a little further north from Los Cabos, into the Mexican desert, where there was a stable. At the stable, our guide already had six horses saddled. Aside from me, my mom, and my grandma, there was a mom and a son who wanted to ride as well. Our guide spoke in broken english, and was a true vaquero. He had some decorated chaps, a dark handlebar mustache, some white curled-point cowboy boots, a traditional (and very colorful) poncho sweater, and an even more decorative sombrero. My mom and grandma were even more nervous when they saw him, because they knew we’d be going on a legitimate ride, and not just some slow-going wander on the beach. But I was even more excited, because I wanted nothing more than a good ride. I was saddled on a huge bay gelding. He was taller than everyone else’s horse, and once everyone was on a horse, the vaquero led us out into the Mexican desert.

He wanted everyone to trot their horses, but no one except me seemed to be brave enough. He’d ride his horse around us like a circling shark, chanting “Rapido, rapido, rapido!” over and over again. The mom and her son just nervously smiled and said “no thank you.”, and my grandma had nothing but fear behind her sunglasses, but our guide persisted until finally everyone was going at a slow trot.

15 minutes into the ride, we made it to the beach. We stopped in the shade of some huge seaside boulders, where our guide helped each of us get off our horse. I was the only one who got off on my own, while everyone else was too afraid to dismount alone because of how tall those horses were.

On the beach, we were allowed to stretch our legs and stand in the warm beach water, though none of us ventured further into the ocean than ankle-deep. I’m not sure how much time passed before the vaquero was calling us to get back to our horses. My grandma was excited that we were heading back.

I got back into my saddle without assistance, while everyone waited for the vaquero’s help to get on. Once everyone was in the saddle and walking again, he turned back and began to ask who wanted to “go very rapido”. I was the only one who volunteered, so he motioned me to hold back my reins while he led everyone a little further off. I stood in the stirrups and waited as the guide brought everyone a good quarter mile away. As he did this, I heard the sound of a distant motor. I looked behind me, and on a sandy ridge was a guy on an ATV. This whole time, he was following us to take pictures that'd we'd end up buying after the ride, and was also there to make sure no one fell off their horse or got lost. He rode down the sandy bluff and waited near me.

“You’re very brave, girl!” he said to me in a standard American accent, “When he says he wants to go fast, he means it!”

I recognized his voice and his build. He was one of the guys who checked us in at the tour bus stop, and was actually born and raised in the States, though most of his family was Mexican. I gave him a small smile, but said nothing. I just stared forward again, squinted to see the horses through the heat waves emanating off the sandy beach, and took in a deep breath as the vaquero trotted back to me. I had no fear, only excitement.

The vaquero stopped his horse beside me, and through hand gestures and broken english, challenged me to a race. If I beat him to the rest of the group, I’d earn bragging rights, but if he beat me, he was allowed to call me “lento” the rest of the ride, which is “slow” in Spanish. I nodded my head and accepted the challenge. He tightened his sombrero’s chin strap, stood up in the stirrups, and after counting down from “tres”, he kicked his horse to go.

Instinctively, my horse took off too, and with one hand on the reins and the other holding onto the saddle horn, I silently rode forward. Kicking and shouting at a horse in a gallop just distracts them and makes them slower, and my horse already knew what to do. Pretty soon, I was stirrup-to-stirrup with the vaquero, and neither of our horses wanted to give up their place. When we made it to everyone else, we were tied. I didn’t get bragging rights, and the vaquero couldn’t call me lento. It was a win-win in my book.

I returned home to the States once again, and after waiting a year and a half for an opportunity, I was finally able to go to my great uncle’s to ride Smudge. By then, Smudge was a little less wild, though he still had a lot of flight in him. I made sure he knew what I was doing before I threw my leg over the saddle, and pressed down on my white cattleman’s hat. I had hunted a turkey for Thanksgiving, and replaced the bright peacock tail feather tip I had in my hatband, with a small iridescent feather from my turkey.

That day, I rode Smudge hard in his round-pen. He had been very antsy before, and needed to be ridden. He fought the reins a little bit, and sometimes spooked, but I never fell off. I kept my boots firmly planted in the stirrups, one hand on the reins, and a free hand to keep my balance. By the time we were done, he was panting heavily and was ready to rest. I fed him plenty of grain, loaded him up into the horse trailer with Apache, and turned him out with Apache in the summer pasture. That was the last time I saw Smudge.

I’ve only ridden once more since, and that was on the back of an old mare who didn’t share my riding style. She still needed to be guided with both hands, while I’m used to horses who only need one hand holding the reins. It was fun and all, but not my best ride ever, especially since it was really hard to revert back to the basics, and it was my first ride in a new saddle. Riding in a brand new saddle is hard on a rider's back and legs. Like a lot of things, saddles need to be broken in before they become comfortable.

It still sucked to lose her though when she was put down on the last evening of summer this year. I found it peculiar that her name was Summer, and she died as the last rays of the final summer sun dipped below the western mountains. It’s almost as if God was putting my cowgirl days to rest along with Summer, but I refuse to let her be the last horse I ever hold the reins to.

The lifestyle of ranching and riding is in my blood. To let Summer be my last horse would be beyond a tragedy. I come from ancestors who were cowboys, and I even grew up around them. My grandpa Lyle is a cowboy, though he never worked cows on horseback. He worked cattle on foot and in his old pickup truck. He rode his horse to elementary school and tamed the wilder ones for fun. My grandpa Bob was a true cowboy before he lost his ability to ride. He used to work cows on horseback, but even when he lost his ability to ride, he would watch as his kids and grand kids worked the cattle instead. One could argue that I’m a cowgirl myself. I’ve never worked cattle on horseback, but I’ve helped to calm stampedes on foot, and I’ve ridden and worked with horses of all kinds. While my cowboy hats have changed over the years, my love for the simple life of ranching hasn’t.

It's true that I was born and raised in the city, but that doesn't mean I wasn't born with a country spirit. Truth is, the only way people can tell I'm from the city is by my address. In every other way, I'm just like my family. I prefer the simple life, and I enjoy the hard work that comes with farming and ranching. Sure, I could get good grades if I go straight to college, but as of now, I plan on mastering a couple trades before I get my degrees. In this day and age, trades are high in demand while students with law and writing degrees struggle to find work and pay of their debt. I'd much rather spend a life in the saddle than in an office cubicle, that's for sure.

I will return to the wide open countryside. I will get back in the saddle one day. I will tame the reins of another horse, just like my ancestors on both sides have done since the beginning. The wrangler way of life is in my blood just as much as hunting is. Sometimes the days are hard, and every rider gets bucked off at least once, but it's worth it, and I miss it everyday. I just need to find ways to feed that passion, which I will one day, hopefully very soon.